Lunar New Year

Lunar New Year, or the Spring Festival, is a festival that celebrates the beginning of a new year on the traditional lunisolar Chinese calendar. Marking the end of winter and the beginning of spring, this festival takes place from Chinese New Year’s Eve, the evening preceding the first day of the year, to the Lantern Festival, held on the 15th day of the year.

Lunar New Year is one of the most important holidays in Chinese culture. It has influenced similar celebrations in other cultures, commonly referred to collectively as Lunar New Year, such as the Losar of Tibet, the Tết of Vietnam, the Seollal of Korea, the Shōgatsu of Japan and the Ryukyu New Year. It is also celebrated worldwide in regions and countries that house significant Overseas Chinese or Sinophone populations, especially in Southeast Asia. These include Singapore, Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. It is also prominent beyond Asia, especially in Australia, Canada, France, Mauritius, New Zealand, Peru, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States, as well as in many European countries.

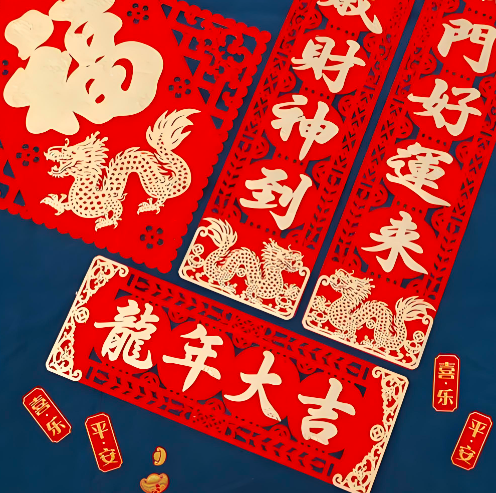

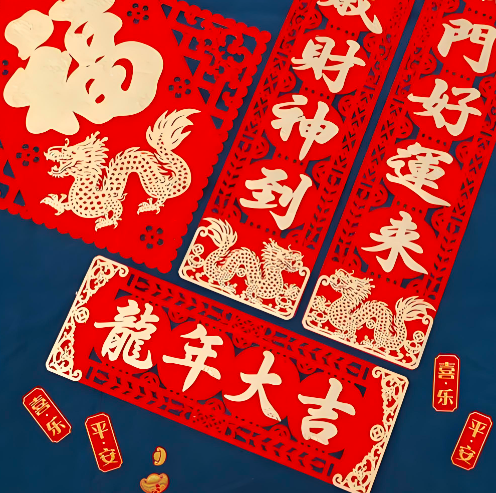

The Chinese New Year is associated with several myths and customs. The festival was traditionally a time to honour deities as well as ancestors. Within China, regional customs and traditions concerning the celebration of the New Year vary widely, and the evening preceding the New Year’s Day is frequently regarded as an occasion for Chinese families to gather for the annual reunion dinner. It is also a tradition for every family to thoroughly clean their house, in order to sweep away any ill fortune and to make way for incoming good luck. Another practised custom is the decoration of windows and doors with red paper-cuts and couplets. Popular themes among these paper-cuts and couplets include good fortune or happiness, wealth, and longevity. Other activities include lighting firecrackers and giving money in red envelopes.

Names

In Chinese, the festival is commonly known as the “Spring Festival” (traditional Chinese: 春節; simplified Chinese: 春节; pinyin: Chūnjié), as the spring season in the lunisolar calendar traditionally starts with lichun, the first of the twenty-four solar terms which the festival celebrates around the time of the Chinese New Year. The name was first proposed in 1914 by Yuan Shikai, who was at the time the interim president of the Republic of China. The official usage of the name “Spring Festival” was retained by the government of the People’s Republic of China, but the government of the Republic of China based in Taiwan has since adopted the name “Traditional Chinese New Year”.

The festival is also called “Lunar New Year” in English, despite the traditional Chinese calendar being lunisolar and not lunar. However, “Chinese New Year” is still a commonly-used translation for people of non-Chinese backgrounds. Along with the Han Chinese inside and outside of Greater China, as many as 29 of the 55 ethnic minority groups in China also celebrate Chinese New Year. Korea, Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines celebrate it as an official festival.

Mythology

According to legend, Chinese New Year started with a mythical beast called the Nian (a beast that lives under the sea or in the mountains) during the annual Spring Festival. The Nian would eat villagers, especially children in the middle of the night. One year, all the villagers decided to hide from the beast. An older man appeared before the villagers went into hiding and said that he would stay the night and would get revenge on the Nian. The old man put up red papers and set off firecrackers. The day after, the villagers came back to their town and saw that nothing had been destroyed. They assumed that the old man was a deity who came to save them. The villagers then understood that Yanhuang had discovered that the Nian was afraid of the color red and loud noises. The tradition grew as New Year approached, and the villagers would wear red clothes, hang red lanterns, and red spring scrolls on windows and doors, and use firecrackers and drums to frighten away the Nian. From then on, the Nian never came to the village again. The Nian was eventually captured by Hongjun Laozu, an ancient Taoist monk.

Traditional food

A reunion dinner is held on New Year’s Eve, during which family members gather for a celebration. The venue will usually be in or near the home of the most senior member of the family. The New Year’s Eve dinner is very large and sumptuous and traditionally includes dishes of meat (namely, pork and chicken) and fish. Most reunion dinners also feature a communal hot pot as it is believed to signify the coming together of the family members for the meal. Most reunion dinners (particularly in the Southern regions) also prominently feature specialty meats (e.g. wax-cured meats like duck and Chinese sausage) and seafood (e.g. lobster and abalone) that are usually reserved for this and other special occasions during the remainder of the year. In most areas, fish (simplified Chinese: 鱼; traditional Chinese: 魚; pinyin: yú) is included, but not eaten completely (and the remainder is stored overnight), as the Chinese phrase “may there be surpluses every year” (simplified Chinese: 年年有余; traditional Chinese: 年年有餘; pinyin: niánnián yǒu yú) sounds the same as “let there be fish every year.” Eight individual dishes are served to reflect the belief of good fortune associated with the number. If in the previous year a death was experienced in the family, seven dishes are served.

Other traditional foods consist of noodles, fruits, dumplings, spring rolls, and Tangyuan which are also known as sweet rice balls. Each dish served during Chinese New Year represents something special. The noodles used to make longevity noodles are usually very thin, long wheat noodles. These noodles are longer than normal noodles that are usually fried and served on a plate, or boiled and served in a bowl with its broth. The noodles symbolize the wish for a long life. The fruits that are typically selected would be oranges, tangerines, and pomelos as they are round and “golden” in color, symbolizing fullness and wealth. Their lucky sound, when spoken, also brings good luck and fortune. The Chinese pronunciation for orange is 橙 (chéng), which sounds the same as the Chinese for ‘success’ (成). One of the ways to spell tangerine(桔 jú) contains the Chinese character for luck (吉 jí). Pomelos are believed to bring constant prosperity. Pomelo in Chinese (柚 yòu) sounds similar to ‘to have’ (有 yǒu), disregarding its tone, however it sounds exactly like ‘again’ (又 yòu). Dumplings and spring rolls symbolize wealth, whereas sweet rice balls symbolize family togetherness.

Red packets for the immediate family are sometimes distributed during the reunion dinner. These packets contain money in an amount that reflects good luck and honorability. Several foods are consumed to usher in wealth, happiness, and good fortune. Several of the Chinese food names are homophones for words that also mean good things.

Many families in China still follow the tradition of eating only vegetarian food on the first day of the New Year, as it is believed that doing so will bring good luck into their lives for the whole year.

Like many other New Year dishes, certain ingredients also take special precedence over others as these ingredients also have similar-sounding names with prosperity, good luck, or even counting money.

Festivities

During the festival, people around China will prepare different gourmet dishes for their families and guests. Influenced by the flourished cultures, foods from different places look and taste totally different. Among them, the most well-known ones are dumplings from northern China and Tangyuan from southern China.

Practices

Red envelopes

Traditionally, red envelopes or red packets (traditional Chinese: 紅包; simplified Chinese: 红包; Mandarin pinyin: hóngbāo; Hokkien Pe̍h-ōe-jī: âng-pau; Hakka Pha̍k-fa-sṳ: fùng-pâu), alternatively known as lai see particularly in Cantonese speaking areas (Chinese: 利是 / 利市 / 利事; Cantonese Yale: laih sih; pinyin: lìshì), are passed out during the Chinese New Year’s celebrations, from married couples or the elderly to unmarried juniors or children. During this period, red packets are also known as yasuiqian (壓歲錢; 压岁钱; yāsuìqián), which was evolved from a homophonous phrase yasuiqian (壓祟錢; 压祟钱; yāsuìqián), literally meaning “money to suppress evil spirits”. According to legend, a demon named Sui would pat a child on the head three times on New Year’s Eve, causing the child to have a fever. In response, parents wrapped coins in red paper and placed them next to their children’s pillows. When Sui approached, the flash of the coin scared him away. Since then, on every New Year’s Eve, parents have wrapped coins in red paper to protect their children.

Red packets almost always contain money, usually varying from a couple of dollars to several hundred. Chinese superstitions favour amounts that begin with even numbers, such as 8 (八, pinyin: bā), a homophone for “wealth”, and 6 (六, pinyin: liù), a homophone for “smooth”—but not the number 4 (四, pinyin: sì), which is a homophone of “death”, and is, as such, considered unlucky in Asian culture. Odd numbers are also avoided, as they are associated with cash given during funerals (帛金, pinyin: báijīn). It is also customary for bills placed inside a red envelope to be new.

The act of asking for red packets (Mandarin: 討紅包; tǎo hóngbāo, Cantonese: 逗利是; dauh laih sih) wouldn’t be turned down by a married person as it would mean that he or she would be “out of luck” in the new year. Red packets are generally given by married couples to the younger non-married members of the family.[85] It is customary and polite for children to wish elders a happy new year and a year and a year of happiness, health, and good fortune before accepting the red envelope.[85] Red envelopes are then kept under the pillow and slept on for seven nights after Chinese New Year before opening because that symbolizes good luck and fortune.

春节

春节,或称农历新年,是根据传统的中国农历庆祝新年开始的节日。作为冬季结束与春季开始的标志,这个节日从农历大年三十(除夕)开始,延续至正月十五的元宵节。

春节是中国文化中最重要的节日之一,它也对其他文化产生了影响,通常被统称为农历新年。例如,西藏的洛萨尔节、越南的春节、韩国的春节(설날)、日本的正月以及琉球的新年庆祝活动。春节在世界各地华人或使用中文的社区中广泛庆祝,尤其在东南亚地区,包括新加坡、文莱、柬埔寨、印度尼西亚、马来西亚、缅甸、菲律宾、泰国和越南。此外,在亚洲以外地区如澳大利亚、加拿大、法国、毛里求斯、新西兰、秘鲁、南非、英国和美国,以及许多欧洲国家也十分流行。

春节与许多传说和风俗习惯相关,传统上是祭祀神灵和祖先的时刻。在中国境内,各地春节庆祝活动和习俗多种多样。除夕之夜通常是家庭团聚的重要时刻,家人共进年夜饭。传统习俗还包括彻底清扫房屋,以扫除厄运并迎接好运。此外,人们会在窗户和门上贴红色的剪纸和春联,主题多为福气、财富和长寿等。其他习俗还包括燃放鞭炮以及赠送红包。

春节与传统习俗

春节与众多传说故事和传统习俗息息相关。这一节日最初是为了祭祀神灵和缅怀祖先而设立的。在中国,不同地区对春节的庆祝方式存在着很大的差异。然而,无论地域,除夕夜通常被视为家庭团聚的时刻,家人们会在这一天齐聚一堂,享用一年一度的团圆饭。

另一个重要的传统是彻底清扫房屋,目的是扫除霉运,为迎接新一年的好运腾出空间。此外,人们还会在窗户和门上贴上红色剪纸和对联,这些装饰品通常围绕福气、财富和长寿等主题。

春节期间的其他活动包括燃放鞭炮和派发红包,这些习俗既表达了对新年的祝福,也增添了节日的喜庆氛围。

名称的由来

在中文中,春节通常被称为“春节”(繁体字:春節;简体字:春节;拼音:Chūnjié)。根据农历,春季的开始以立春(二十四节气之一)为标志,春节正好在这一时段左右。这个名称最早于1914年由时任中华民国临时大总统袁世凯提出。中华人民共和国政府沿用了“春节”的官方名称,而中华民国(台湾地区)政府则采用“传统春节”这一名称。

在英文中,这个节日也被称为“Lunar New Year”(农历新年),尽管中国的传统历法是阴阳历而非纯阴历。然而,对于非华人背景的人来说,“Chinese New Year”(中国新年)仍是常用的翻译。除了汉族人,境内的55个少数民族中有多达29个民族也庆祝春节。此外,韩国、越南、新加坡、马来西亚、印度尼西亚和菲律宾也将其作为官方节日。

神话传说

据传说,春节起源于一种名为年的神秘怪兽,它栖息在海底或深山中,每到春节便会袭击村庄,尤其是儿童。有一年,村民们决定躲避年兽。就在村民躲藏之前,一位老人出现并表示他会留守对付年兽。老人用红色的纸装饰房屋并燃放鞭炮。第二天,村民们发现他们的村庄没有受到破坏,便认为那位老人是一位神灵。他们意识到,年兽害怕红色和巨响。于是,村民们开始穿红衣、挂红灯笼、贴红春联,并用鞭炮和鼓声驱赶年兽。从此,年兽再也没有回来。

传统食品与寓意

年夜饭通常在除夕夜进行,家人团聚一同庆祝。年夜饭十分丰盛,通常包括肉类(如猪肉和鸡肉)和鱼类。南方的年夜饭中常见腊肉(如腊鸭、腊肠)和海鲜(如龙虾和鲍鱼)。鱼(鱼,拼音:yú)是常见的菜肴之一,但不会被吃完,寓意“年年有余”(年年有鱼)。春节期间的传统食品包括面条、水果、饺子、春卷以及汤圆(又称甜米团)。每道菜肴都蕴含着特殊的寓意。

汤圆:象征家庭团圆和亲密无间。

长寿面:用于制作长寿面的面条通常是非常细长的小麦面条。这些面条比普通面条更长,通常以煎炒或煮汤的形式呈现。长寿面象征着对长寿的祝愿。

水果:常选的水果有橙子、橘子和柚子,这些水果因其圆形和“金色”的外观象征着圆满与财富。它们的发音也带来吉祥的寓意:

橙子(橙,chéng)与“成功”(成,chéng)谐音;

橘子(桔,jú)含有象征“吉祥”的字(吉,jí);

柚子(柚,yòu)与“有”(有,yǒu)和“又”(又,yòu)音同,寓意常有或再来。

饺子和春卷:象征财富,因为它们的形状与元宝或金条相似。

春节素食与食材寓意

在中国,许多家庭仍然保持春节初一吃素的传统。他们相信,初一食用素食可以为整年的生活带来好运和福气。

与其他春节菜肴一样,初一的素食食材也有特殊的象征意义。一些食材因其名称与繁荣、好运甚至财富相关的词语谐音而备受青睐。例如:

- 发菜(fàcài):“发菜”与“发财”谐音,寓意生意兴隆和财富增长;

- 年糕(niángāo):“糕”与“高”同音,象征年年高升;

- 莲子(liánzǐ):寓意连生贵子,表达对家庭人丁兴旺的期望。

通过这些象征性的食材和菜肴,人们在春节期间祈求新的一年中生活顺遂、事业兴旺和家庭幸福。

风俗活动

春节期间,中国各地的人们会为家人和客人准备各种美食,不同地区的菜肴风味各异。最为著名的有北方的饺子和南方的汤圆。

习俗

红包

春节期间,红包(繁体:紅包;简体:红包;拼音:hóngbāo)由已婚者或长辈分发给未婚的年轻人或儿童。红包中一般装有金额为偶数的崭新纸币,避开不吉利的数字(如“4”)。分发红包时,晚辈需向长辈拜年,以表达祝福和感谢。

红包通常被压在枕头下,象征好运。

红包中通常装有金钱,金额范围从几元到几百元不等。根据中国传统文化的数字吉利观念,红包金额一般以偶数开头,例如:

- 8(八,拼音:bā):谐音“发”,寓意财富;

- 6(六,拼音:liù):谐音“顺”,寓意顺利。

但4(四,拼音:sì)因谐音“死”而被视为不吉利,因此红包金额中通常避免出现4。奇数也被避免使用,因为它们通常与丧礼(帛金,拼音:báijīn)相关。此外,放入红包的钞票通常要求是崭新的,象征喜庆和美好。

在春节期间,向已婚人士讨要红包(普通话:讨红包,拼音:tǎo hóngbāo;粤语:逗利是,拼音:dauh laih sih)不会被拒绝,因为拒绝可能被认为会导致新年“运气不好”。红包一般由已婚人士分发给家庭中未婚的年轻人或儿童。

在接受红包之前,孩子们通常会向长辈表达新年祝福,如祝愿新年快乐、幸福健康和好运连连,以示礼貌和感激之情。红包在收到后,通常被放在枕头下压七天,象征着好运与福气长存。